Alexander the Great: Hero or Villain?

Alexander the Great in the Alexander Mosaic. The mosaic depicts Alexander chasing the Persian king Darius during the Battle of Issus.

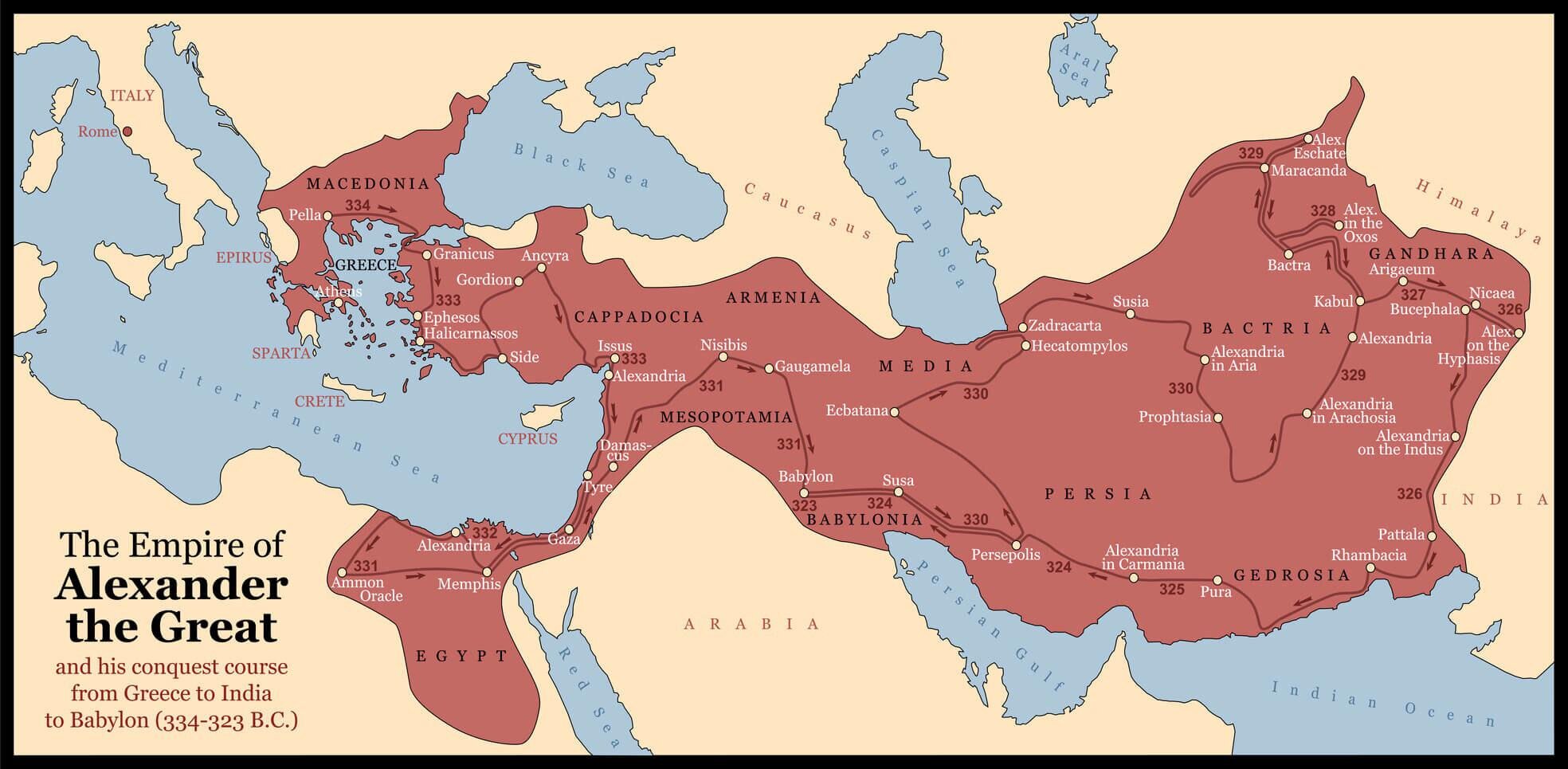

Who has not heard of Alexander the Great? He is one of the most important figures in history and is easily the most famous Greek to have ever lived. Many might not know much about him, but we all know the name. However, it is no wonder why his name and legacy has lived on for more than 2,000 years. Alexander was able to conquer the whole known world. He founded an empire, which although short-lived, was one of the most diverse empires to have ever existed, stretching across three continents. His empire might not have survived for too long, but the Hellenistic culture that Alexander brought with him to the lands he conquered would remain for hundreds of years. He brought Greek civilisation that extended as far as India. He never lost a battle, and his tactics are still studied by military academies today. By the time of his sudden death at the age of 32, his multicultural empire spanned from the hilly farmland of Macedonia to the lush, green plains of the Punjab. With such great achievements, it’s hard not to admire the man. But not all people share such admiration for Alexander. In the West, he is known as Alexander the Great. In the East, he is known as Alexander the Accursed, the bogeyman, among other unflattering titles. Many claim that Alexander was no better than Genghis Khan. His slaughter and enslavement of the people of Thebes, the destruction of Tyre, and the burning down of the ancient city of Persepolis are all unfortunate events that happened during his conquests, events that many people claim are valid reasons not to call Alexander “the Great”. So, was Alexander the hero of the West who brought civilisation to the lands he conquered, or was he a villain whose memory should be associated not with greatness but rather with evil and terror?

To answer this rather complicated question, we must take a step back to really understand the character of Alexander and his accomplishments as a conqueror. Alexander (Αλέξανδρος) was born on 356 BC in Pella, the capital of the Macedonian Kingdom. His father, Philip, was the king of Macedonia. Philip deserves much admiration for the way he was able to bring Macedonia from a backwater hillbilly country, full of sheep herders, to the strongest power in Greece. His military and political reforms shaped Macedonia into a nation that had no other equal in Greece. He laid the foundation for Alexander’s conquests. He was the only reason why Alexander didn’t have to conquer the whole of Greece before attacking Persia. Thanks to Philip’s military reforms such as the introduction and effective implementation of the phalanx into the Macedonian army, Alexander had with him the strongest professional fighting force in the world. Without Philip, Alexander would most definitely not have conquered land after land so easily. Alexander’s mother, Olympias, was a very powerful and cunning woman. If Philip was responsible for Alexander’s tactical and practical knowledge, Olympias was responsible for making Alexander the Alexander we all know. From a very young age, Alexander was told by his mother stories about his ancestor Achilles and how he was able to make countless Trojan souls bite the dust and defeat the legendary Hector, the most feared Trojan. Moreover, one of his ancestors on his father’s side was none other than the legendary Heracles (Hercules) himself. Olympias probably told Alexander how it was his destiny to be as great as Achilles and Heracles, how his noble bloodline demanded that he be something great. Alexander was also led to believe that his birth was a miracle of the gods. According to Olympias, Zeus slept with her, taking the form of a snake. After this affair, Olympias became pregnant and gave birth to Alexander. Being spoon-fed all this by his mother since he was just a boy, one wonders if this left a mark on Alexander’s psyche.

Philip II (Left) and Olympias (Right)

Alexander was extremely intelligent. As a boy, he loved to read and study the great works of Homer and historians like Herodotus and Xenophon. His favourite book was the Iliad, the tale of Achilles and the Trojan War. Philip wanted Alexander to be different from all the other Macedonians of his age. Macedonia was seen as a back-water nation by the other Greek states. They were barely even considered Greek. They were known as the “milk-drinking sheep-herders” of Greece. Philip wanted to shape Alexander into a man who no Greek could rival in terms of character and intellect. To do this, he hired the greatest intellect of Greece, Aristotle, to be Alexander’s private tutor. Aristotle shaped Alexander’s already clever and sharp mind into something much greater. He instilled within Alexander the importance of philosophy and knowledge. He taught Alexander how it is important to understand the deeper meaning of things, to look beyond the appearances. He also taught Alexander the importance of virtue, and how every good man needed to be a virtuous man. Under Aristotle, Alexander gained a deeper appreciation for Homer. Aristotle even gave him an annotated copy of the Iliad. It is later said that Alexander always kept this book along with a dagger under his pillow during his conquests. Aristotle played a pivotal role in helping Alexander become someone who not only surpassed all others in terms of intellect and knowledge, but someone who could also understand the nuances and intricacies of the world he lived in.

Artist’s depiction of Alexander and Aristotle

Alexander’s first experience with ruling a kingdom started when he was just 16. As Philip was waging a war against Byzantion, Alexander was left in charge of Macedonia. He was able to drive back the invading Illyrians and colonise their lands. He even created a new city there called Alexandropolis. Later, Alexander would join his father in the Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC) where he would demonstrate his tactical brilliance and skill on the battlefield. After the battle, Philip was able to bring all of Greece under his rule with the exception of Sparta, who Philip probably ignored on purpose. He was then declared hegemon (ήγεμών) or “supreme ruler” of the League of Corinth. He soon announced his plans to invade Persia, to punish them for what they did to Greece during the Greco-Persian Wars.

Alexander later had a falling out with Philip. Philip was intending to marry another woman named Cleopatra (not the the lover of Marc Antony), hoping to have a son with her. During the wedding party, Alexander became enraged after Attalus, a friend of Philip, praised the gods that Philip would finally have a legitimate son. This was an insult to Alexander since he was only half-Macedonian as his mother Olympias was from Epirus. Alexander attacked Attalus, and when the drunken Philip tried to intervene, he slipped from the table he was standing on and fell to the ground. Alexander shouted, “Look now, men! Here is the one who was preparing to cross from Europe into Asia; and yet he fails in trying to jump from couch to couch!”. Philip then had Alexander and his mother exiled. Alexander stayed in Illyria, having dropped his mother off in Epirus, for just six months until he was asked to return by Philip. Philip could not afford to lose someone so politically and militarily knowledgeable as Alexander.

In 336 BC, before Philip planned to begin his invasion of Persia, he was assassinated by one of his bodyguards, Pausanias, in a public theatre in Aigai. Pausanias was later chased down and killed by some of Alexander’s companions. The reasons behind Pausanias killing Philip are still debated today. Roman historian Livy claims that Pausanias was raped by one of Philip’s friends, Attalus, and Philip did not do anything about it. Pausanias was deeply insulted by this and decided to punish the king for this injustice, essentially making Philip’s death an honour killing. This is generally accepted to be the reasons behind Philip’s death. But some historians claim that the assassination, especially given the history of Philip and Alexander, seems very suspicious. Philip was intending to marry another woman and have a son with her, a pure-blooded Macedonian son. Alexander had more than enough reason to order the death of Philip, or at least be involved in some way. His position as the successor to the Macedonian throne could be threatened if Philip had a son, which was of course unacceptable for Olympias and Alexander. Although we may never know the truth, it’s important to understand all the points-of-view regarding the assassination. Nevertheless, Alexander, just 20 years old, was proclaimed King of Macedonia in the public theatre of Aigai.

Artist’s depiction of Phillip’s assassination

Alexander’s accession to the throne and consolidation of power was not so smooth and bloodless. He spent the first months of his rule brutally eliminating all potential enemies and rivals. Olympias also helped him in this regard. After it was clear that no one could stand up to Alexander in Macedonia, he then had to deal with the Greek states that rebelled after hearing of Philip’s death which included Thebes, Athens, and Thessaly. Alexander wasted no time and raced south with his cavalry. At first, all the states that rebelled against him were quick to reaffirm their loyalty. Alexander was given the title of hegemon and the supreme command for the invasion of Persia. After consolidating his power in the south, he hurried north to deal with the Thracian rebellion. During this campaign, some Greek states, most notably Athens and Thebes, once again rebelled against Alexander. The man leading the anti-Alexander rhetoric was an Athenian orator named Demosthenes. He made fiery speeches about why they should unite against Alexander, who he often called “boy”. Once Alexander, defeated the Thracians, he swept south with his army to reconsolidate his power. Thebes was the only major state that defiantly rejected Alexander’s order of submission. This enraged Alexander and here we see the first hint of what was to come to cities that refused Alexander as their ruler. After a rather long siege, Alexander’s troops were able to break into the city. Alexander then ordered all grown males to be executed and all the women and children to be sold as slaves. He spared only those that sought refuge in the House of Pindar (a famous poet who praised the Macedonians). He then had the entire city burned to the ground. After the destruction of Thebes, Athens cowered back and accepted Alexander’s rule. It was clear to all - anyone who stood in Alexander’s way would be crushed.

Finally, with all of Greece (with the exception of Sparta) under his rule, Alexander began the long-awaited invasion of Persia. In 334 BC, he led his army across the Hellespont into Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey). It was the beginning of one of the world’s greatest conquests. The Persians decided to face Alexander’s army at the Granicus River. It was the first major battle of the campaign. Alexander was able to demonstrate his tactical superiority to the Persians, as well as his fearless leadership. He always fought in the thick of the battle, always leading by example. The Battle of the Granicus River was a decisive victory for Alexander, giving him all of Asia Minor. The Persian Empire was still a very big and rich power, and it began to gather its resources and armies to fight Alexander. Alexander spent the rest of 334 BC and the spring of 333 BC destroying key Persian naval bases, most notably Halicarnassus and Miletus. He could only take these bases after long, bloody sieges. After securing the bases and weakening Persian naval power, Alexander marched through Asia Minor. In Gordium, Alexander came face-to-face with the Gordian Knot. Legend had it that the one who could untie the knot would be ruler of Asia. Alexander, annoyed that he could not untie the knot, took out his sword and simply cut the knot in half. This says a lot about his character. If he doesn’t get want he wants through peaceful solutions, he simply takes it with force. Alexander then moved southeast, arriving at the Nur Mountains. Darius, King of Kings, emerged behind Alexander’s army and forced Alexander to fight. It was time to end this Greek’s foolish game once and for all. Alexander’s army was outnumbered by 2 to 1. To his right were mountains, and to his left was the sea. The two armies met at Issus. The battle was a bit tougher for Alexander. The main phalanx army was being slowly driven back for a time by Greek mercenaries fighting for the Persians. But Alexander saw this and charged at the Persian centre with his elite companion cavalry, causing panic and disarray. The Greek mercenaries, panicking over what was happening behind them, were now being driven back by the phalanx. Alexander chased King Darius, who was desperately trying to escape the wrath of the seemingly mad “boy-king”. The Alexander Mosaic, found in the House of Faun in Pompeii, depicts this scene. Alexander’s left flank, commanded by his trusted general Parmenion, was still holding back the elite Persian cavalry, although at a great cost. However, as the news of Darius fleeing from the battle spread, they too gave up the fight. What followed was an utter slaughter as the Greeks chased down the fleeing Persians. It is said that there were so many Persian dead, that the bodies were used by the army to cross over a ravine. Darius was so confident of his victory that he even brought his mother, wife, and children. Alexander captured them, but treated them with great care and respect.

Artist’s depiction of Alexander and his Companion Cavalry

Alexander spent much of 332 BC subduing the Phoenician coastal cities. This effectively ended the Persian navy’s presence in the Mediterranean. All the cities accepted Alexander’s rule willingly (or unwillingly) except for one - Tyre. When Tyre refused to submit to Alexander, along with killing his envoys and barring him from visiting the newly-built Temple of Melqart (Heracles), Alexander became furious at the Tyrian defiance and ordered a siege. The siege was different in that it was bloodier and “tougher” than the others Alexander had commanded previously. Because Tyre was an island, Alexander actually built an entire causeway that connected the mainland to the island so that his troops could lay siege to it. This causeway and the ancient ruins of Tyre actually still exist today in Lebanon. The whole time Alexander’s engineers were building the causeway, they were harassed by Tyrian fire ships and archers. Alexander even had to start all over again when the first causeway was destroyed by the Tyrians. He then ordered his own navy be built so that they could counter the Tyrian ships and prevent attacks on the causeway. When Alexander was finally able to send troops to attack the Tyrian defences, the once proud Tyrians who were so confident about their walls and their island isolation began to flee in every direction and prostrated themselves in front of every statue of their gods, begging for salvation. When Alexander and his troops made a breach in one of the walls, they burst into the city and slaughtered every single Tyrian they could find, another example of how merciless Alexander could be. Those who were in the Temple of Melqart, which included the king of Tyre, were pardoned by Alexander. Tyre essentially ended up being given the same treatment as Thebes. The Siege of Tyre was a lot like Alexander’s Troy, with the Tyrians being the Trojans and Alexander being Achilles.

Picture of Alexander’s causeway. You can see the ancient city of Tyre on the left.

Besides Tyre, Gaza also rejected Alexander’s rule. Again, after three bloody attempts to overcome the mound the city was situated on, Alexander and his troops were finally able to breach the city’s defences and slaughter and enslave everyone inside. According to the Roman historian Quintus Curtius Rufus, the eunuch of the city, Batis, was killed after being dragged by Alexander’s chariot around the city. If this is true, Alexander was clearly emulating the way his ancestor Achilles dragged Hector’s body before Troy.

In late 332 BC, Alexander entered the ancient land of Egypt. The Egyptians viewed him as a liberator instead of a conqueror. They were more than happy to accept Greek rule over the Persians. The Persians never had a good history with Egypt. The Egyptians saw the Persians as oppressors who had no respect for Egyptian religion or customs. Roman historian Livy claimed that the drunk Cambyses II was even responsible for killing the sacred Apis Bull, which if true further highlights Persian negligence and apathetic behaviour towards Egyptian customs. In Memphis, Alexander was named Pharaoh of Egypt, marking the first line of Greek kings in Egypt. He then founded the city of Alexandria. The city still exists today and was once regarded as a sanctuary of knowledge and learning, being home to the great Library of Alexandria (the most famous of which was accidentally burned down by the Romans). In the desert oasis of Siwah, Alexander was proclaimed Son of Amon, Son of Zeus. This further convinced Alexander of his divine heritage and destiny.

A part of the Luxor Relief. Alexander is shown right.

In 331 BC, Alexander and his army marched out of Egypt and into the deeper lands of the Persian Empire. It was during this time that Alexander received a letter from King Darius. The Persian king promised Alexander his daughter in marriage, half the empire, and a big sum of gold in exchange for peace. But Alexander didn’t want half, he wanted all of it. Alexander wrote a letter to Darius in response to the offer. The description of the contents of the letter come from the Greek historian Arrian. “Your ancestors came into Macedonia and the rest of Greece and treated us ill, without any previous injury from us”…“For you sent aid to the Perinthians, who were dealing unjustly with my father”…“My father was killed by conspirators whom you instigated, as you have yourself boasted to all in your letters”…“As your agents destroyed my friends, and were striving to dissolve the league which I had formed among the Greeks, I took the field against you, because you were the party who commenced the hostility. Since I have vanquished your generals and viceroys in the previous battle, and now yourself and your forces in like manner, I am, by the gift of the gods, in possession of your land. As many of the men who fought in your army as were not killed in the battle, but fled to me for refuge, I am protecting; and they are with me, not against their own will, but they are serving in my army as volunteers. Approach me therefore as the lord of all Asia. But if you are afraid you may suffer any harsh treatment from me in case you come to me, send some of your friends to receive pledges of safety from me…“But for the future, whenever you send to me, send to me as the king of Asia, and do not address to me your wishes as to an equal; but if you are in need of anything, speak to me as to the man who is lord of all your territories”…“But do not run away. For wherever you may be, I intend to march against you”.

Alexander learned that Darius had assembled a great army at Gaugamela (near modern-day Mosul in Iraq). Eager to end Persian military might once and for all, he marched straight to Gaugamela. King Darius chose the battlefield with great care. He ordered his troops to pick out every piece of weed and remove every rock, things that could hinder the use of the chariots. His army was massive, being about 70,000-80,000 men as compared to Alexander’s 40,000. It was also not entirely Persian. Many troops came from modern-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Iraq, and Armenia. It was a reminder of how diverse the Persian empire really was. The Battle of Gaugamela really was Alexander’s masterpiece. How could his small army defeat an enemy that was twice the size? Alexander knew that he could not attack the Persians with a head-on assault. His army could easily be encircled and annihilated. So, he decided to lead his right flank (cavalry and skirmishers) away from the battlefield. The Persians, perplexed by this move, decided to mirror Alexander’s movements and follow his cavalry. As a result, the Persian army’s centre was weakened as troops and cavalry were sent to confront Alexander. When Alexander saw that his plan had worked, he ordered his flank to charge the Persian cavalry in order to keep them busy. Darius, thinking that this was the decisive moment, ordered his scythed chariots to crash into the Macedonian lines. However, Alexander taught his men how to confront these cars of death. As the chariots came charging at the Macedonian line, the phalanxes simply opened “lanes”, allowing the chariots to pass through. They would then close the lanes and trap the chariots, killing the drivers. This effectively made the chariot an obsolete weapon that can no longer be used in any effective manner on the battlefield ever again. Alexander ordered his main army to charge the Persian centre, weakened by the lack of troops. He led his personal companion cavalry into the thick of the Persian army, aiming to kill Darius once and for all. The Persians could not handle the sudden ferocity of the Macedonian attack. They decided to turn and run, being cut down the whole time by the pursuing Greeks. Darius was leading the rout. Alexander could not continue his pursuit of Darius as he was informed of the dire situation of his left flank commanded by his trusted general Parmenion. The Persians were taking a toll on Parmenion’s cavalry. The left flank was barely holding on. Alexander reluctantly gave up his pursuit of Darius and decided to save Parmenion. When his cavalry charged the Persians, and as news of Darius’s flight spread, the Persian cavalry decided to flee for their lives as well. The Battle of Gaugamela was a complete victory for Alexander. Although he was not able to kill Darius, the Persian army was no longer an effective fighting force, and Darius was losing the trust of his generals.

Sketch of a Macedonian phalanx formation

Alexander was now able to traverse the Persian empire without any real fear of Darius striking back. He led his army to the ancient city of Babylon, which was the capital of the Persian empire at the time. In late 331 BC, he entered the city in triumph and was recognised as the empire’s rightful ruler. Babylon was one of the seven wonders of the world. Its architecture and beauty must have stunned the Macedonians. The “milk-drinking sheep herders” of Greece were now rulers of Babylon. But Alexander did not stay in Babylon for a long time and in 330 BC marched towards Susa, the once capital of the Persian empire and the location of the royal throne. Alexander was ceremoniously named King of Persia as he took his seat on the throne. From Susa, he led his army towards the ceremonial capital of the Persian empire, Persepolis, literally “City of the Persians”. Before he entered the city, he was stopped by a small Persian army led by Ariobarzanes at a mountain pass known as the Persian Gate. The Persians fought bravely and held up Alexander’s advance. However, Alexander led his troops around the Persians, using a secret path unbeknownst to the enemy. Appearing behind them, he slaughtered the Persian troops along with Ariobarzanes. This battle is uncannily similar to the famous Battle of Thermopylae where a small mainly-Spartan force held up the massive army of Xerxes. Just like how the Persians were defeated by Alexander at the Persian Gate due to the discovery of a secret path, the Persians defeated the Spartans at Thermopylae the same way. With the small Persian force overcome, Alexander finally entered Persepolis. Here we see another one of the disasters that took place during Alexander’s conquests. Accounts differ on what exactly happened, it is generally thought that Alexander, drunk from a party and urged on by his friends, ordered the city to be burnt. Some say that Alexander later regretted this decision as he feared it could tarnish his image as a “liberator”. Others say that Alexander was satisfied by this and cited the burning of Athens by the Persians in 480 BC to be a legitimate reason for retribution. Nevertheless, the burning of Persepolis was a tragedy and one wonders what sort of great architectural discoveries could have come up today had the city not been burnt.

From Persepolis, Alexander led his army north into Media and towards the winter capital of Ecbatana, where Darius was taking refuge. Upon learning of Alexander’s advance, Darius fled East. He hoped to raise a new army to confront Alexander. However, his plans never came to be as he was assassinated by one of his governors, Bessus, who then proclaimed himself to be the rightful ruler of Persia. Alexander, instead of mutilating Darius’s body, decided to honour it. He ordered the body of Darius to be given a proper funeral worthy of a Persian king, and for the body to be buried in the royal tombs of Persepolis. At this point, Alexander decided to take a “break” and reorganise his vast new empire. He kept the same system of governance as the Persians, which was to divide the empire into satrapies with each satrapy having its own governor or “satrap”. He even allowed certain Persian satraps who had proved their loyalty to keep their posts. Alexander’s decision to retain the Persian system of rule speaks volumes of how effective Persian governance really was. The Persians laid the foundation for how future empires would be governed. It was thanks to Alexander who introduced this Persian system of governance to the Western world, where it would live on in the forms of the Roman and British empires.

Artist’s depiction of the burning of Persepolis

Alexander continued his march East. His goal was to find and kill Bessus and to subjugate the eastern provinces. First, Alexander led his army to Aria, located in modern-day Afghanistan, to deal with the traitorous Persian governor Satibarzanes and his revolt. After crushing the revolt, Alexander marched south to Phrada. Here is where we see another example of the more ruthless side of Alexander. Philotas, son of Alexander’s most trusted general Parmenion, supposedly confessed that he knew of a plot to kill Alexander but never informed Alexander about it. Alexander, not wanting to die like his father Philip, ordered Philotas to be executed. He then sent some assassins to Ecbatana, where Parmenion was serving as governor, to kill Parmenion before news of Philotas’s death reached him, which could have possibly turned him against Alexander. It is almost certain that the deaths of Parmenion and Philotas were rather unsettling for Alexander’s generals and troops. They were already a little put-off by Alexander’s seemingly increasing interest in Eastern customs, or what the Greeks would call “barbarian”. In 329 BC, Alexander continued his pursuit of Bessus. Along the way he founded a city known as Alexandria Arachosia, one of dozens of cities that bear his name. At Kunduz in modern-day northern Afghanistan, Bessus was betrayed by one of his men and given over to Alexander. Accounts differ on the manner of Bessus’s death. Quintus Curtius Rufus says that Bessus was crucified while Arrian claims that he was beheaded in Ecbatana. Killing a king, especially in a very secretive manner, was seen as a backward and even sacrilegious act that called for severe punishment.

After successfully hunting down Bessus, Alexander pushed further north into Sogdia (modern-day Tajikistan). He had to deal with local Sogdian revolts and had to take several towns by siege. It was a particularly hard campaign as the Greeks were not used to fighting tribal armies that relied on skirmishes and hit-and-run tactics rather than the conventional warfare of the Persians. After successfully putting an end to the Sogdian resistance, Alexander reached the Jaxartes River and founded a city named Alexandria Eschate, meaning “Alexandria the Furthest”. This was the limit of the Persian empire. The frontier of the Jaxartes River was often raided by Scythian tribes from the north. To put an end to the raids, Alexander lured the Scythians to the Jaxartes where a big cavalry battle ensued. The result was a victory for Alexander and an end to the Scythian raids.

In 328 BC, Alexander led his army back south, stopping at Maracanda. Here we see how Alexander’s temper can suddenly explode, often causing harm to others in the process. Cleitus the Black (he was not black) was an unfortunate victim of this temper. Cleitus was one of Alexander’s trusted generals who served under Philip as well. In the Battle of the Granicus River, as Alexander was fighting hand-to-hand with his troops, he was charged by two Persian nobles named Rhoesaces and Spithridates. As Alexander was fighting off Rhoesaces, Spithridates was bringing down his sword on Alexander and was about to hit him until Cleitus came in just in time and cut off Spithridates’s arm. He saved Alexander from a much earlier death so the king could go on to conquer more lands. During a wine-party at Maracanda, it is said that the drunk Alexander began exclaiming how his achievements were much greater than his father Philip’s. Before this, Alexander also began to reorganise the satrapies and lines of command. Cleitus was given command of a detachment of Greek soldiers and was appointed satrap of Sogdia and Bactria. Cleitus did not like this new appointment as he felt this was a lowly position. When he heard Alexander boasting of his achievements, he interjected and said that Philip was a far better man than Alexander, and that without Philip Alexander would not have been where he was now. Alexander, already heavily drunk, took this as an insult and called his guards. Cleitus pushed Alexander over the limit when he mentioned how Alexander was only half-Macedonian and was probably an illegitimate son of Philip. Alexander had enough, he quickly grabbed a spear and hurled it at Cleitus, killing him instantly. It is said that shortly after Cleitus’s death, Alexander realised what he had done and became quite depressed, full of remorse.

Artist’s depiction of Alexander killing Cleitus.

Alexander seemingly became much more arrogant and detached from his Macedonian comrades. His increasing interest in Persian customs and dress as well as encouraging his Macedonians to adopt these customs greatly concerned his generals and army. One example of this was when Alexander tried to have his companions and soldiers perform the royal Persian tradition of proskynesis, where one had to completely prostrate himself when in the presence of the king. This outraged his fellow Macedonians and they voiced their disapproval of this request. The freedom-loving Greeks could not bring themselves to bow down to a king. Alexander had to back off and obey the wishes of his countrymen. The killing of Philotas and Parmenion and now recently Cleitus, all three being very notable Macedonian men, also did not help improve Alexander’s image among the army. His soldiers were also tired, not so much physically, but more so by continuous conquest. They were so many thousands of miles from home, fighting tribes on the eastern-most border of the Persian empire. They were originally on this conquest of revenge, eager to get back at the Persians for what they did to Greece during the Greco-Persian Wars. But now, this was no longer about revenge or bringing justice, it was about following the ambitions and dreams of their king who wanted nothing less than to conquer the known world. How far will their king take them? When will they go home? Will they ever even see home again?

Alexander led his army to Bactra. It was here where yet another plot to assassinate Alexander was uncovered. This time it was involving the young pages, children of Macedonian nobles who serve the king. One of the pages, Hermolaos, was revealed to be the ringleader of the plot. He was supposedly angered by Alexander over an apparent injustice. Alexander wasted no time with them and had the traitorous pages stoned to death. It is safe to say that these plots took a toll on Alexander, making him more suspicious and “unsafe” by the day. He started to see everyone around him as “potential enemies”, all vying for the Macedonian throne, now the most powerful position in the world.

Besides the plot of the pages, Alexander fell in love with one of the Bactrian noblewomen named Roxanna and decided to marry her. While the marriage was probably done with political intent, some historians believe that Alexander really was captivated by Roxanna’s beauty and was overcome with love. Again, many of his fellow Macedonians were put-off by this. How can the great Macedonian king marry some barbarian girl? Nevertheless, the marriage sealed Alexander’s alliance with the Bactrian king and secured his rear. He was now able to push on into the legendary land of India, a land only visited by the mighty Heracles himself.

Alexander and Roxanna

The Persian empire’s most eastern provinces of Gandhara, Hindush, Sattagydia, and Gedrosia had yet to recognise Alexander’s rule. This was of course unacceptable for Alexander, and he led his army across the Hindu Kush Mountains, heading towards the Indus River Valley (located in modern-day Pakistan). Alexander entered the Swat Valley in 326 BC and fought a series of skirmishes. He took the settlement of Massaga by siege. It is said that he later fell in love with the queen of Massaga who supposedly bore him a son. He continued east and entered Taxila, near modern-day Islamabad. The king of Taxila decided to form an alliance with Alexander and was allowed to keep his throne. From Taxila, he marched to the River Hydaspes (Jhelum), where his advance was stopped by the king of the Pauravas, Porus. What ensued was a savage battle, the bloodiest and costliest battle of Alexander’s conquests. King Porus proved to be a tough opponent. He and his soldiers fought bravely. His elephants, never seen in such huge numbers by the Greeks, wreaked havoc in the Macedonian lines. Despite the difficulty of the fight, Alexander was still able to outsmart Porus and encircled the Indian army, slaughtering nearly everyone until Porus decided to surrender. It is said that after the battle, Alexander called Porus for a meeting. Alexander is said to have asked Porus, “How, then, do you wish to be treated?”. To which Porus replied, “Treat me as a king ought to be treated”. Alexander was impressed by Porus’s bravery and honour. He decided to let Porus keep his throne and even have him serve as a satrap. The battle allowed Alexander to gain control of the Punjab.

The Battle of the Hydaspes was the most savage battle of Alexander’s conquests

Alexander pushed further into India. He reached the River Hyphasis (Beas) and was forced to stop, not by an enemy army, but by his own troops. They had finally had enough. They had not seen their homes in years. They were tired of fighting battle after battle for Alexander. They had also heard some rumours of massive Indian armies waiting for them. They would not go one step further. Alexander knew that without an army, he was nothing more than a wishful king who wanted to conquer the world. Furious at his army’s cowardliness, he decided to turn back. He followed the Indus river and travelled south towards the sea. Along the way, he led a siege of the capital of the Mallians (today Multan). During the siege, he was hit in the chest by an arrow and became unconscious. His army thought he was dead, until after some risky healing, he appeared before them in front of his tent and was honoured with cheers and shouts of praise. No one can deny that Alexander was a king that few can rival in courage and loyalty to the soldiers. Once Alexander and his army reached the coast, he sent Nearchus and a detachment of ships to reach Persia by sea. Nearchus reached Persia through the Straits of Hormuz and the Persian Gulf. This one of the greatest voyages of exploration as the Greeks had no idea of these waters. As Nearchus was sailing for Persia, Alexander led his army across the Gedrosian Desert, located in modern day Baluchistan, Pakistan. This was a particularly harsh march as the utter heat and shortages of food and water led to many deaths. It is said that once Alexander finally left the desert, half of his army had either died off or run away. Historians debate on why Alexander decided to march through such a harsh terrain when he could have used other routes. Some claim that he wanted to punish his army for their insubordination in India. Others say that this was simply a strategic error on Alexander’s part. And yet there are even some who claim that Alexander wanted to prove his invincibility, that no desert could stop his mighty army. Whatever the reason, Alexander crossed the Gedrosian Desert in 325 BC.

Artist’s depiction of Alexander pouring the only water left in front of his troops. Legend has it that when offered a helmet-full of water, Alexander poured all of it out onto the desert floor in front of his thirsty troops. He suffers what they suffer.

Alexander reached Persepolis in 325 BC. He decided to take a short pause and execute several viceroys and governors who had behaved unjustly during his conquest of India. He reached Susa in 324 BC, where he arranged a mass-marriage of Macedonian officers and noblemen to 80 Persian princesses. It is said that the Persian noblewomen were so beautiful, that it was hard to even look at them. This mass-marriage was obviously intended to strengthen the Greco-Persian bonds. Alexander also took the time to pay off all of his soldiers’ debts and to order 30,000 youths from across the empire to begin training. They were to be the new generation of Macedonian soldiers, trained and educated in the Greek fashion. At Opis, Alexander’s army mutinied once again. They were offended at Alexander’s apparent preference for Persian customs and Persian advisors. He himself was beginning to look more Persian than Greek. Alexander had to leaders of the mutiny executed and made an emotional speech in front of his army. He cited the achievements of Philip and how his rule brought Macedonia from a sheep-herding state to the most powerful nation in Greece. He mentioned the countless battles he fought with his army and the countless wounds he had on his body. When his soldiers grieved, he grieved. When his soldiers rejoiced, he rejoiced. The soldiers who died during the conquest were honoured back home. Their families were exempt from taxes and statues were built in their honour.

“Go back and report at home that your king Alexander, the conqueror of the Persians, Medes, Bactrians, and Sacians; the man who has subjugated the Uxians, Arachotians, and Drangians; who has also acquired the rule of the Parthians, Chorasmians, and Hyrcanians, as far as the Caspian Sea; who has marched over the Caucasus, through the Caspian Gates; who has crossed the rivers Oxus and Tanais, and the Indus besides, which has never been crossed by any one else except Dionysus; who has also crossed the Hydaspes, Acesines, and Hydraotes, and who would have crossed the Hyphasis, if you had not shrunk back with alarm; who has penetrated into the Great Sea by both the mouths of the Indus; who has marched through the desert of Gadrosia, where no one ever before marched with an army; who on his route acquired possession of Carmania and the land of the Oritians, in addition to his other conquests, his fleet having in the meantime already sailed round the coast of the sea which extends from India to Persia - report that when you returned to Susa you deserted him and went away, handing him over to the protection of conquered foreigners.”

“Perhaps this report of yours will be both glorious to you in the eyes of men and devout I ween in the eyes of the gods. Depart!”

Alexander’s charm and skill as an orator led his army to have an emotional reconciliation with him. From Opis, Alexander marched to Ecbatana. It was here where Alexander’s childhood friend and most trusted general, Hephaistion, died of a fever. Alexander was deeply affected by this loss. He went days without eating and ordered a period of mourning across the empire. After Ecbatana, Alexander won a small campaign against the Cossaea, mountain raiders who had always caused trouble for the Persians. Alexander then returned to Babylon in 324 BC. Here he met embassies from distant peoples who had come from as far as Gaul (France). Roxanna was also revealed to be pregnant. It was of course unknown whether the baby would be a boy or girl. Alexander began planning his next campaign into Arabia. It was at this time that Alexander developed a heavy fever. Historians debate how Alexander got the fever. Some say it was natural while others say it was part of an assassination plot. Both are plausible reasons for something we will never learn the answer to. Alexander the Great died a few days later, aged 32. It is said that before his death, his generals gathered around him and asked him who the successor to the empire would be. Legend has it that Alexander, barely able to speak, yelled out with all his remaining strength, “To the strongest!”. If this is true, it gives us an insight as to how Alexander viewed his empire. If he was not worthy of ruling it, no one will.

Sick Alexander listening to one of the physicians

As no one knew who the successor to the empire would be, the generals began vying for the strongest parts of it. Each wanted a share of the spoils. The empire Alexander carved out was massive, stretching from Greece to modern-day Pakistan. However, it was a very unstable empire that needed a leader. Without one, it was almost certain that it would not survive. The empire ended up being split into multiple smaller empires that would live longer than Alexander’s empire itself. Each of the new empires were ruled by one of Alexander’s generals - Ptolemy (Egypt), Lysimachus (Northeastern Greece), Seleucus (Iran, Iraq, and Syria), Cassander (Greece), and Antigonus (Asia Minor and Palestine/Judea). Each of these generals would fight each other for years to come. These wars would be known as the Wars of the Diadochi. In the ensuing power vacuum, Alexander’s mother Olympias and his son with Roxanne were all murdered. Alexander’s own sarcophagus was hijacked by Ptolemy on its way to Greece. The last known location of the sarcophagus was in the royal tombs of Alexandria. The current location is now unknown and has become one of history’s greatest mysteries.

Now that we have understood Alexander’s history and have some insights into his character, it is time to answer the question at hand - Alexander the Great, hero or villain? We have now officially entered the “grey area of history” - morality. We are essentially asking whether Alexander was a good or bad person. The case for him being considered “bad” is rather compelling. There is no doubt that he killed thousands of people during his conquests. His ruthlessness to some of the cities like Tyre and Thebes resulted in terrible suffering for the innocent population. However, when answering such a question, you have to ask yourself, “what would I have done?” What would you have done if you were Alexander? Sure, if Tyre decided to reject your rule, you could simply bypass them and allow their city to survive. You would save countless lives. However, you will have to live with fear as you worry that Tyre might create some sort of revolt that you would have to deal with in the future. Letting Tyre go is a risk that Alexander could not and would not take. It didn’t matter how many people would die, what mattered was that the threat was eliminated, and his empire could survive. This leads to another key point that many people seem to forget about the ancient world - power. Power was everything. If you wanted to survive, let alone thrive in the ancient world, you had to have power. You had to demonstrate to others that you were not someone to mess around with. If you didn’t prove your strength to others, people would take advantage of you and they would eliminate you. Alexander had to prove to the people he conquered that if they stood in his way, they were going to suffer. The modern ideals of morality did not exist in Alexander’s time. Good and wrong were seen in a completely different manner than they are today. The fact remains that we cannot judge Alexander, or anything in the ancient world, with a modern 21st century mindset.

Alexander’s empire was one of the largest in the world

Now that we have seen the case for Alexander’s villainy, let’s look at him in a different perspective. We often judge historical figures based on their legacies. Alexander’s name and legacy still lives on today after more than 2,000 years. The Hellenistic culture that he spread across the countless lands he conquered remained for hundreds of years. He introduced the Greek ideas of virtue, education, theatre, sport, and democracy to the East. Still today, we are finding ancient coins in Afghanistan with the names of the kings written in Greek. Alexandria, the Egyptian city Alexander founded in his name, would later become one of the world’s greatest educational centres. Some of Alexander’s tactics, in particular the various flanking manoeuvres, are taught in military schools all over the world. His accomplishments as a conqueror greatly influenced other historical figures such as Caesar and Napoleon. The spread of the Greek language across the empire later led to the creation of Koine Greek (Common Greek). Greek became the English of the ancient world. We can say that it was thanks to Alexander that the New Testament of the Bible was originally written in Greek and not Hebrew.

Alexander the Great was a phenomenon. Ever since he had been a young Macedonian boy who had dreamt of conquering the world, he had never given up and had kept his focus on the ultimate goal. Whenever he ran into an obstacle, be it an enemy army or hostile city, he overcame it. He never allowed anyone or anything to stop him from realising his dream, no matter what the cost. The question of whether Alexander can be considered a hero or villain is something that can never be answered. These questions of morality are almost never applicable to the ancient world. What we can say is how great the legacy of individuals like Alexander was and its shaping of the world for millennia to come. I mentioned in the beginning that everyone has heard of the name “Alexander”. Alexander the Great might not have conquered the whole world, as he so desperately wished, but his name has conquered the minds and imaginations of everyone everywhere on this planet, something very few individuals have been able to achieve in the history of mankind.

Bibliography

Rufus, Q. C., Atkinson, J. E., & Yardley, J. (2009). Histories of Alexander the Great. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Livy, Yardley, J., & Briscoe, J. (2018). History of Rome. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Arrianus, F., & Brunt, P. A. (2014). Anabasis of Alexander. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Freeman, Philip. Alexander the Great. Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2011.

Plutarchus. Plutarch's Lives. Harvard Univ. Press, 2007.

Green, Peter. Alexander of Macedon, 356-323 B A Historical Biography. University of California Press, 2012.

Renault, Mary. The Nature of Alexander the Great. Penguin, 2001.

Heckel, Waldemar, and Lawrence A. Tritle. Alexander the Great: a New History. John Wiley & Sons, 2009.

Bowden, Hugh. Alexander the Great: a Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2014.